In This Section:

Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse

- The Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse

- Intimate Partner Violence by Race and Ethnicity

- Intimate Partner Violence and Older Women

- Intimate Partner Violence and Reproductive Health

- Domestic Violence Fatality Review Teams

- Policies to Address Violence Against Women

- Unmet Needs for Services and Supports

- Domestic Violence and Child Custody Cases

- Basic Statistics on Rape and Sexual Violence

- Rape and Sexual Violence by Race and Ethnicity

- Sexual Violence on College Campuses

Violence and Safety Among Teen Girls

- Prevalence of Stalking and Common Stalking Behaviors

- State Statutes on Stalking

- Civil Protection Orders

- Gun Laws and Violence Against Women

Violence and Harassment in the Workplace

- Intimate Partner Violence and the Workplace

- State Employment Protections for Victims of Domestic Violence

- Workplace Sexual Harassment

Violence and Safety Among LGBT Women and Youth

The Consequences of Violence and Abuse

Toward the Creation of Safer Communities

Introduction

Over the last few decades, the nation has made considerable progress in addressing the violence and abuse many women experience at the hands of partners, acquaintances, and strangers. Since the 1970s, the movement to end partner abuse has led to many reforms in the United States (and worldwide) on the part of federal agencies, the criminal justice system, child welfare programs, and others that have increased protections for women and children (Aron and Olson 1997; Stark 2012a).

Despite this progress, threats to women’s safety continue to profoundly affect their economic security, health, civic engagement, and overall well-being. For many women, experiences with violence and abuse make it difficult to pursue educational opportunities (Riger et al. 2000) and to perform their jobs without interruption (Logan et al. 2007; Riger et al 2000). Although contextual factors such as poverty status and racial/ethnic background correlate with the prevalence of victimization, no one remains immune (Benson and Fox 2004; Breiding et al. 2014). Violence and abuse affect women and girls from all walks of life.

This report examines many of the major topics that advocates in this area have prioritized, including intimate partner violence and abuse, rape and sexual assault, stalking, workplace violence and sexual harassment, teen dating violence and bullying, gun violence, and human trafficking. Because quantitative data on these issues are limited, especially at the state level, the report provides an overview of available data but does not rank the states on selected indicators or calculate a composite index. (IWPR hopes to develop a composite index in this area in the future and to address additional issues in the field, including military sexual assault and immigrant women’s experiences with violence and harassment.) The report also considers state laws intended to protect survivors, where information on these laws has been compiled and analyzed by experts in the field. Such laws may increase women’s safety but may also fall short of providing the full range of protections that women need.

Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse

The Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse

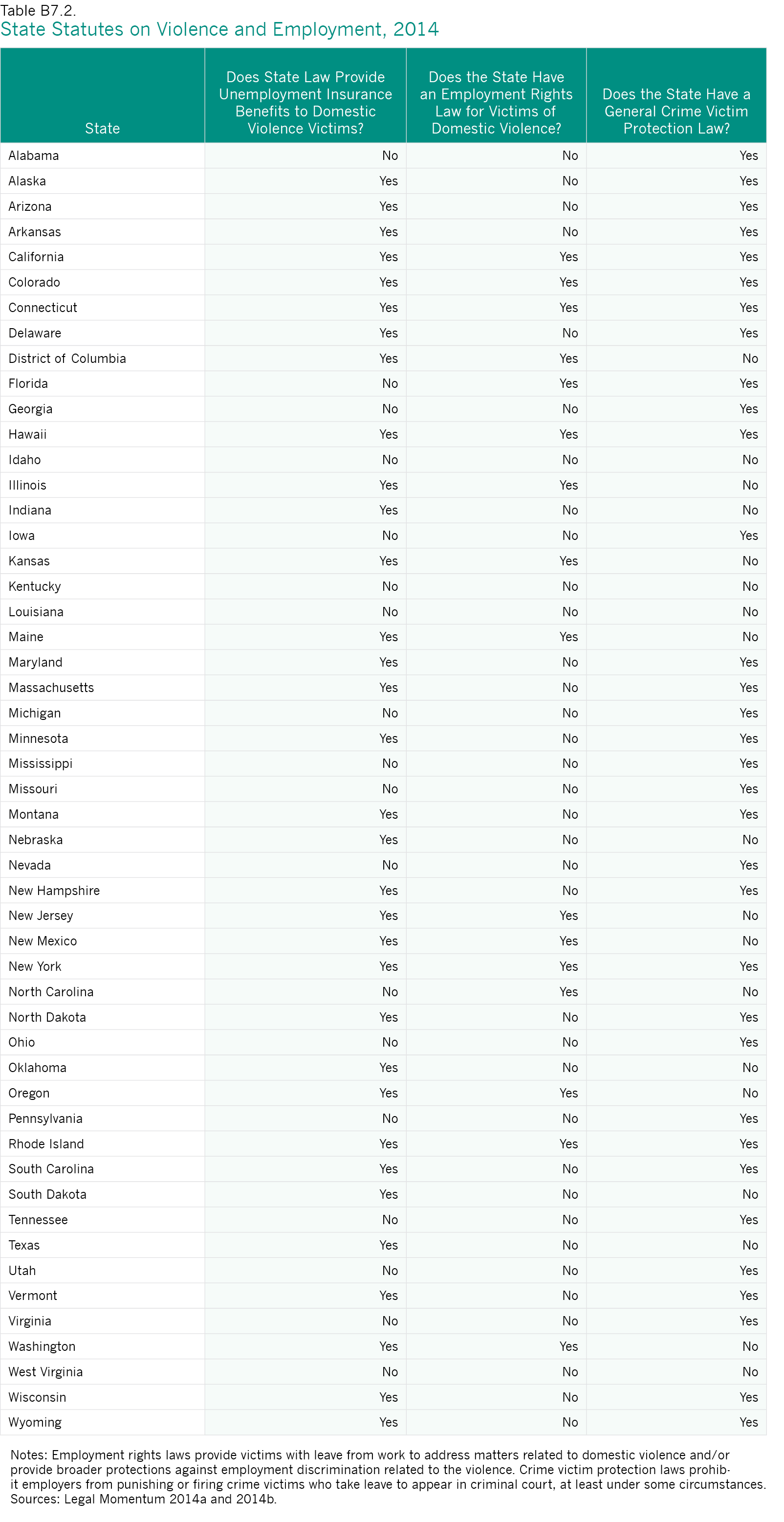

Domestic (or intimate partner) violence is a pattern of behavior in which one person seeks to isolate, dominate, and control the other through psychological, sexual, and/or physical abuse (Breiding et al. 2014). According to analysis of the 2011 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), nearly one in three women (31.5 percent) experiences physical violence by an intimate partner at some point in her lifetime. A smaller, but still substantial, share experience partner stalking (9.2 percent), rape (8.8 percent), or other sexual violence by an intimate partner (15.8 percent; Figure 7.1).1 In addition, nearly half of all women experience, at some point in their lifetimes, psychological aggression from an intimate partner. This aggression—which is arguably the most harmful component of intimate partner violence (Stark 2012b)—includes both expressive aggression, such as name calling, and attempts to monitor, threaten, or control their partner’s behavior (Figure 7.1).

Many victims experience more than one of these forms of harm. Often, perpetrators combine attempts to subjugate and control victims with physical and sexual violence, creating a condition of “entrapment” that undermines victims’ physical and psychological integrity (Stark 2012b). Nearly four in ten female victims interviewed for the 2010 NISVS reported having experienced more than one form of partner violence (Black et al. 2011). Approximately 14 percent said they experienced physical violence and stalking; nine percent reported experiencing rape and other forms of physical violence by an intimate partner; nearly 13 percent said they experienced rape, other physical violence, and stalking; and a very small percentage said they experienced both rape and stalking by an intimate partner (Black et al. 2011).

Figure 7.1. Lifetime Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse Among Women by Type of Violence, United States, 2011

Note: Women aged 18 and older.

Source: Breiding et al. 2014. Compiled by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Intimate Partner Violence by Race and Ethnicity

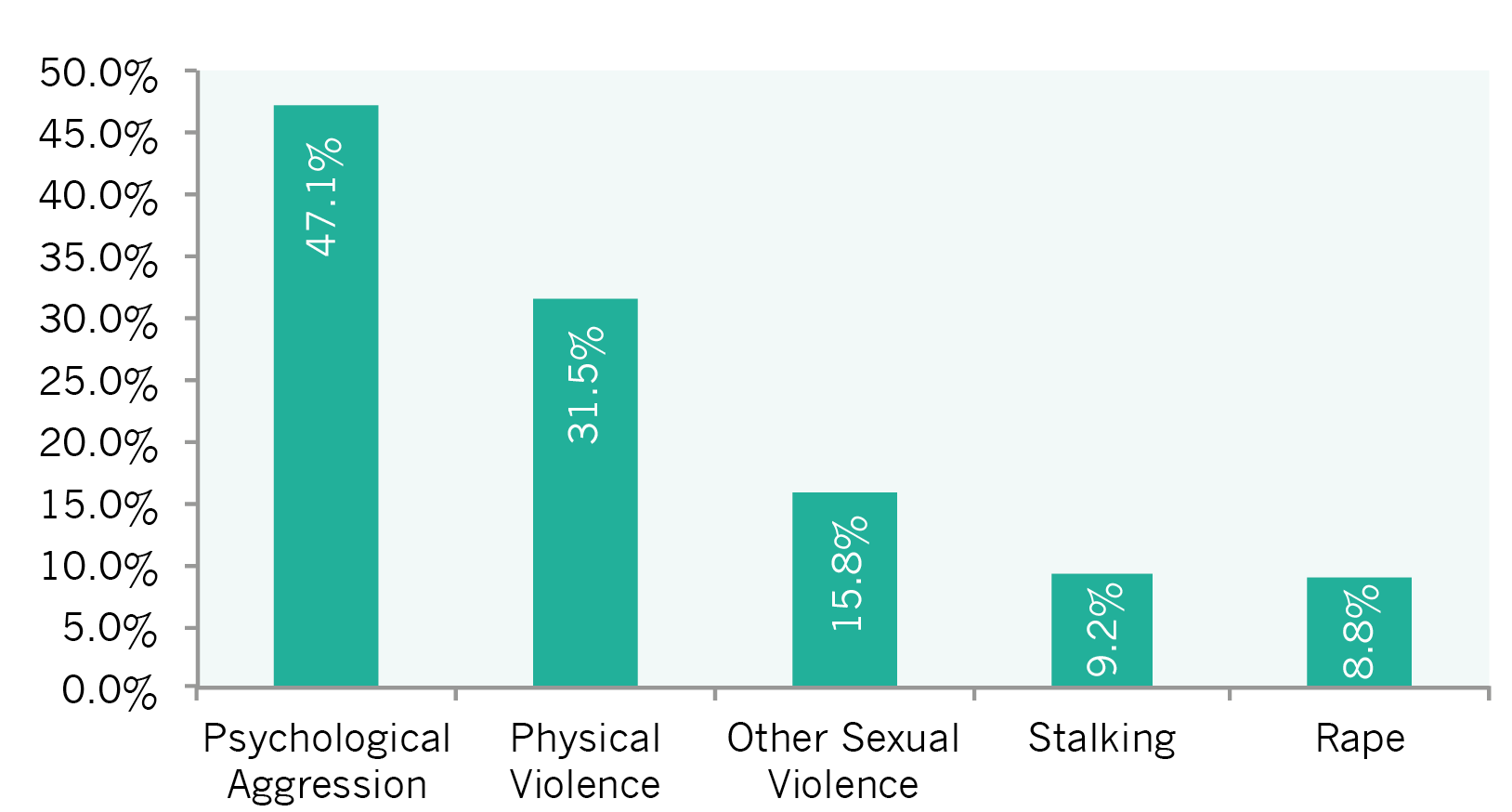

The prevalence of intimate partner violence and abuse varies across the largest racial and ethnic groups. Nationally, it is estimated that more than half of Native American and multiracial women, more than four in ten black women, three in ten white and Hispanic women, and three in twenty Asian/Pacific Islander women (Figure 7.2) have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner (Figure 7.2). An even higher proportion have experienced psychological aggression: more than six in ten Native American and multiracial women report having experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner, as have more than half of black women, more than four in ten white and Hispanic women, and three in ten Asian/Pacific Islander women (Figure 7.2).2

Figure 7.2. Lifetime Prevalence of Physical Violence and Psychological Aggression by an Intimate Partner Among Women, by Race/Ethnicity, United States, 2011

Notes: Women aged 18 and older. Only whites and blacks are non-Hispanic. Hispanics may be of any race or two or more races.

Source: Breiding et al. 2014. Compiled by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Sexual violence within intimate partner relationships also affects a disturbingly large share of the population. Breiding et al. (2014) estimate that about 11 percent of women who identify with two or more races, 10 percent of white women, 9 percent of black women, and 6 percent of Hispanic women have experienced rape by an intimate partner. A larger proportion—27 percent of multiracial women, 17 percent of black and white women, and 10 percent of Hispanic women—have experienced sexual violence other than rape by an intimate partner (Breiding et al. 2014). Data on sexual violence other than rape are not available for Asian/Pacific Islander or Native American women.

Other research indicates that Native American women experience particularly high rates of sexual violence within intimate partner relationships. One study that analyzed rape and sexual assault data from the National Crime Victimization Survey found that Native Americans are two and a half times as likely as whites and African Americans, and five times as likely as Asian Americans, to experience a rape or sexual assault (data are not disaggregated by gender; Perry 2004). Another study found that Native American women are considerably more likely than white or African American women to be victimized by an intimate partner. Nearly four in ten (38 percent) Native American women who have experienced rape or sexual assault were victimized by an intimate partner, compared with about one in four white women and African American women (24 and 23 percent, respectively) and one in five (20 percent) Asian American women (Bachman et al. 2008). The high rates of sexual violence experienced by Native American women are part of a broader pattern in which Native American women disproportionately experience violent crime (Greenfeld and Smith 1999).

Intimate Partner Violence and Older Women

Violence and abuse can affect women of all ages, including in the later stages of life. One study analyzing data from the National Crime Victimization Survey—which focuses on violent crime, not including economic domination or psychological abuse—found that the rate for IPV victimization among older women (aged 50 and older) in the United States is 1.3 per 1,000; while this rate is much lower than the victimization rate for younger women (9.7 per 1,000 women aged 18–24, 12.1 per 1,000 women aged 25–34, and 9.6 per 1,000 women aged 35–49; Catalano 2012a), the prevalence of elder IPV may be higher than the social science literature reports (Rennison and Rand 2003).3 In addition, older women are also at risk for other forms of family violence, including abuse from adult children and from other institutional and noninstitutional caregivers. One statewide study found that unlike younger women, older women were more likely to be abused by nonintimate family members than intimate partners (Klein et al. 2008).

Older women who experience intimate partner or family violence and abuse may face challenges in accessing services and extricating themselves from abusive situations. Adult protective services in all states serve older women who are abused, yet these services focus primarily on frail elderly victims, and most abuse cases do not come to their attention. Shelters and services for abused women are also generally set up to address the needs of younger women with children (Brandl and Cook-Daniels 2011). In addition, older women—who may have been out of the workforce for some time or lack the skills to obtain a living-wage job—may find that leaving their abusive spouse could leave them without financial security and health insurance, at a time when they most need it (Rennison and Rand 2003). Older women who experience violence and abuse may have even fewer options than their younger counterparts.

Intimate Partner Violence and Reproductive Health

Abuse has many effects on women’s reproductive health. The tactics employed by abusers may include not only sexual assault or rape but also reproductive or sexual coercion, including behaviors such as demanding unprotected sex, sabotaging a partner’s birth control, impregnating a partner who does not want to become pregnant, and injuring a partner in a way that can lead to miscarriage (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2013; Chamberlain and Levenson 2012). Analysis of the 2010 NISVS indicates that about nine percent of female survey respondents have had an intimate partner who tried to get them pregnant or stop them from using birth control (Black et al. 2011).

Domestic and sexual violence also puts women and girls at higher risk of sexually transmitted infections and HIV (Decker, Silverman, and Raj 2005; Sareen, Pagura, and Grant 2009; Wingood, DiClemente, and Raj 2000). One study analyzing data from ninth through twelfth grade girls participating in the Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Surveys found that among girls who have been diagnosed with HIV or another sexually transmitted infection, more than half reported having experienced physical or sexual intimate partner violence. Girls experiencing this violence were 2.6 times more likely than nonabused girls to report an STD diagnosis (Decker, Silverman, and Raj 2005).

Domestic Violence Fatality Review Teams

Domestic violence is sometimes fatal: in 2012, 924 women in the United States were killed by their spouse or by an intimate partner (Violence Policy Center 2014). To reduce domestic violence-related deaths, many states have established domestic violence fatality review teams (DVFRTs) that bring together professionals from different fields—including health, education, social services, criminal justice, and policy—to review fatal and near fatal domestic violence cases to identify trends and patterns, offer recommendations, and track the implementation of those recommendations (Sullivan and Websdale 2006). Domestic violence fatality review teams—which vary in their size, composition, and review processes—focus on developing best practices and implementing coordinated, cross-disciplinary approaches to meet the needs of domestic violence survivors and reduce fatalities in their local communities (Sullivan and Websdale 2006). A 2013 report found that 32 states had enacted legislation establishing Domestic Violence Fatality Review teams; some domestic and sexual violence coalitions, state governments, and local municipalities have also developed such teams without legislative direction (Durborow et al. 2013).

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Justice awarded $2.3 million to 12 sites across the country as part of a Domestic Violence Homicide Prevention Demonstration Initiative (DVHP Initiative). Modeled after programs in Maryland and Massachusetts where coordinated teams of service providers, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and health professionals worked together to reduce the domestic violence homicide rate—the initiative aims to identify women who may be in fatally abusive relationships and to monitor high-risk offenders (The White House 2013).

Policies to Address Violence Against Women

Since the 1970s, the movement to end partner abuse has led to many reforms in the United States that help to protect survivors, including criminalizing physical abuse by partners, developing sanctions to hold offenders accountable, and opening emergency shelters that provide supports for victims and their children (Stark 2012a). In addition, child welfare agencies have integrated domestic violence concerns into their services (Aron and Olson 1997), and states across the nation have implemented a range of legal protections for victims of violence. These protections include laws related to stalking offenses, limitations on gun access for perpetrators of intimate partner violence, civil protection orders, and statutes to protect the employment rights of domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking victims, among others.

The first domestic-violence specific federal funding stream—the Family Violence Prevention Services Act (FVPSA)—was enacted in 1984 to fund domestic violence shelters and programs (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2012). Over the last 20 years, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and other federal and state funding streams have provided funding to enhance the response of police, prosecutors, and the court system to partner abuse (Buzawa, Buzawa, and Stark 2012). First passed in 1994, VAWA also established new penalties for those who crossed state lines to injure, stalk, or harass another person and created the National Domestic Violence Hotline, a toll-free number that has served victims across the nation. In addition, VAWA 1994 created legal protections for undocumented immigrant victims of violence whose abusers often use their legal status as a tool of coercion; these protections were strengthened in subsequent reauthorizations of VAWA (Faith Trust Institute 2013; National Network to End Domestic Violence 2013a; Sacco 2014).

The most recent reauthorization of VAWA, which was signed into law in March 2013, extends provisions for victims in multiple ways (Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013). For example, it explicitly includes members of LGBT communities among those eligible for VAWA programs and increases protections for Native American women by empowering tribal authorities to prosecute non-Native American residents who commit crimes on tribal land (National Network to End Domestic Violence 2013a). In addition, VAWA 2013 adds stalking to the list of crimes that make undocumented immigrants eligible for protection (National Organization for Women 2013) and requires colleges and universities to report statistics on domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking in the annual security report that each institution must issue under the Jeanne Clery Act (American Council on Education 2014).

Unmet Needs for Services and Supports

While many domestic violence victims seek assistance from anti-violence programs and services in their local areas, services are not always available to them. In September 2013, the National Network to End Domestic Violence conducted its annual one-day count of domestic violence shelters and services across the country (National Network to End Domestic Violence 2013b). Nationally, 87 percent of all identified local domestic violence service programs were surveyed (1,649 out of 1,905). The programs surveyed served 66,581 adults and children in a single day, offering services such as individual and/or children’s support or advocacy, emergency shelter, court or legal services, and transportation services. On that one day, 9,641 requests for services went unmet, 60 percent (5,778) of which were for housing. Multiple factors contribute to these unmet needs, including reduced funding for domestic violence services and lack of staff resources to administer them (National Network to End Domestic Violence 2013b). The number of unmet needs varies greatly by state, with states that have larger population sizes generally having more instances of unmet needs.

Domestic Violence and Child Custody Cases

Women who experience domestic or intimate partner violence often become involved in contested child custody cases. Domestic violence researchers and practitioners have become increasingly concerned with the outcomes of custody and visitation cases where mothers or their children allege that a father has been abusive. Scholars and practitioners report that courts often do not take this abuse into account (or fail to believe the allegations, seeing them instead as evidence that the mother seeks to “alienate” the child from his or her father) and award access or custody to the abusive parent (Goldfarb 2008; Meier 2010). While the exact number of children who face this outcome is unknown, one study that used data on divorce, family violence, and the outcomes of custody and visitation litigation in cases involving abuse allegations estimates that more than 58,000 children each year are court-ordered into unsupervised contact with an abusive parent following divorce (Leadership Council 2008).

Domestic violence can be minimized or discounted in decisions about custody and visitation in multiple ways. One study found that some courts allow “friendly parent principles”—which give preference to the parent who is more likely to support an ongoing relationship between the child and the other parent—to take precedence over allegations of abuse (Morrill et al. 2005). In addition, research indicates that some custody evaluators lack expertise in domestic violence and fail to report or to adequately assess the nature and effects of this abuse when making their recommendations (Davis et al. 2011; Pence et al. 2012; Saunders, Faller, and Tolman 2011), which play an important role in informing court decisions (Bruch 2002; Saunders, Faller, and Tolman 2011). Evaluators who do consider domestic violence sometimes focus only on physical violence and fail to see a broader pattern of domination and control (Pence et al. 2012). One study that interviewed 23 custody evaluators across the United States found that those who recognized that physical domestic violence could be part of a broader pattern of control were more likely to endorse specific safeguards to protect children—such as supervised visitation, neutral and public drop-off and pick-up locations, and no visitation when safety could not be ensured—than those who held a more incident-based view of domestic violence (Haselschwerdt, Hardesty, and Hans 2011).

Rape and Sexual Violence

Basic Statistics on Rape and Sexual Violence

Sexual violence and rape are alarmingly common and pose a serious threat to women’s health and well-being. One study analyzing data from the 2011 NISVS found that in the United States, 19.3 percent of women are raped at some time in their lives, and 43.9 percent experience sexual violence other than rape (Breiding et al. 2014). Often, the perpetrator is someone the victim knows: almost half of the female rape victims surveyed (46.7 percent) said they had at least one perpetrator who was an acquaintance, and a similar proportion (45.4 percent) said they had least one perpetrator who was an intimate partner (Breiding et al. 2014).

Nearly eight in ten female rape victims were first raped before age 25, and approximately 40 percent were raped before age 18 (Breiding et al. 2014). Victimization at a young age is associated with revictimization later in life. One report analyzing the 2010 NISVS found that more than one-third of women who were raped as minors were also raped as adults, compared with 14 percent of women who had no history of victimization prior to adulthood (Black et al. 2011).

Rape and Sexual Violence by Race and Ethnicity

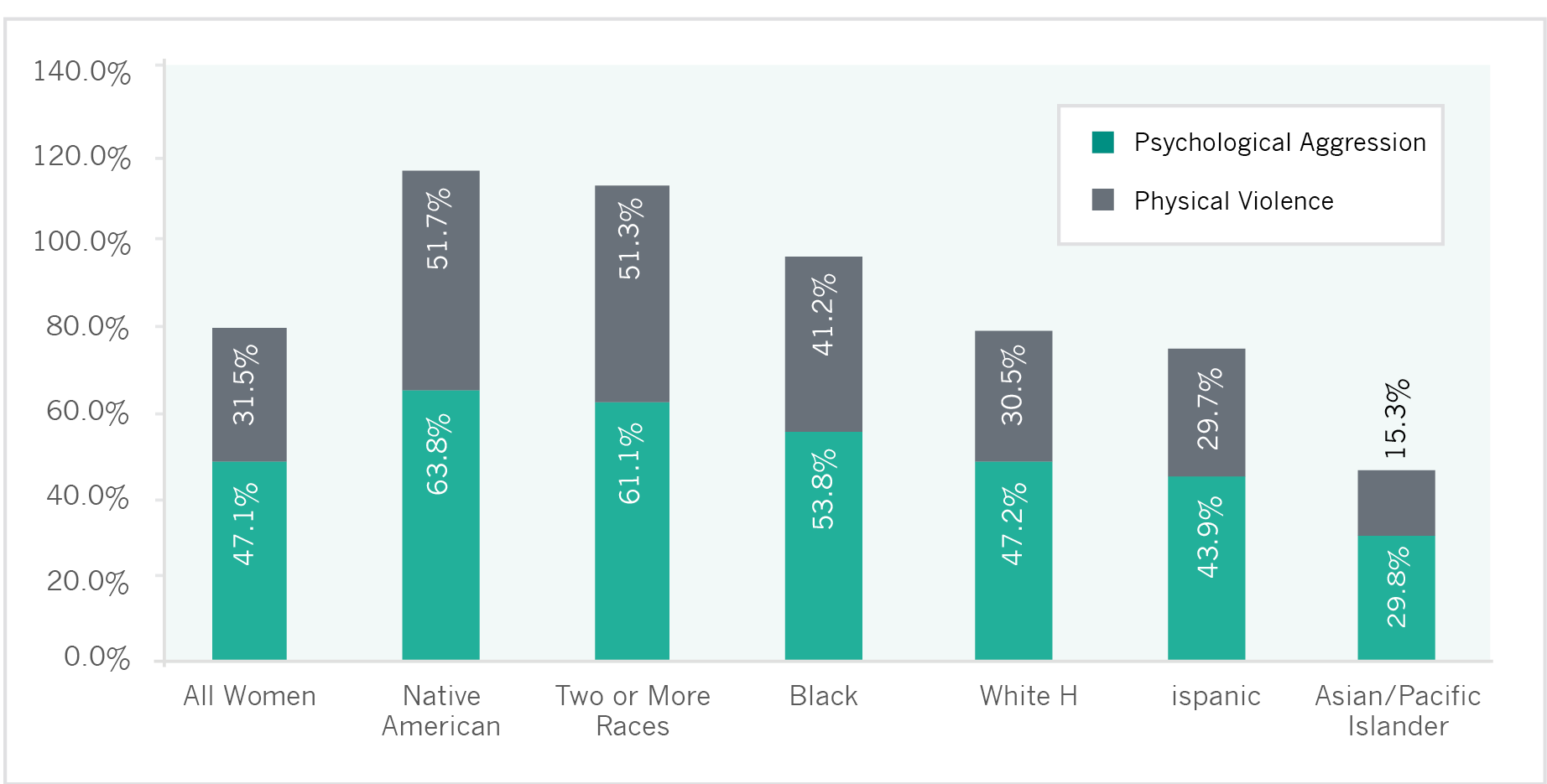

Multiracial and Native American women are more likely to experience rape and sexual violence than other groups of women. Estimates suggest that nearly a third (32.3 percent) of multiracial women, and 27.5 percent of Native American women, are raped at some point in their lifetimes (Figure 7.3). Approximately 64.1 percent of multiracial women and 55.0 percent of Native American women are estimated to have experienced sexual violence other than rape, compared with 46.9 percent of white women, 38.2 percent of black women, 35.6 percent of Hispanic women, and 31.9 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander women (Breiding et al. 2014).4

Figure 7.3. Lifetime Prevalence of Sexual Violence Victimization by Any Perpetrator Among Women, by Race and Ethnicity, United States, 2011

Notes: Only whites and blacks are non-Hispanic. Hispanics may be of any race or two or more races. Data on rape are not available for Asian/Pacific Islanders due to insufficient sample sizes.

Source: IWPR compilation of data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey based on Breiding et al. 2014.

Sexual Violence on College Campuses

Sexual violence on college campuses has gained attention in recent years among policymakers, the public, college and university officials, and others. One survey of more than 6,800 students (5,466 women and 1,375 men) at two large public universities found that about one in five women had experienced an attempted or completed sexual assault while in college (defined to encompass a wide range of victimization types, including rape and other unwanted sexual contact; Krebs et al. 2007). Although this study is not nationally representative, its findings are in line with a 2004 study that analyzed three years of data on a randomly selected sample of students (n=8,567 for the first year, 8,425 for the second year, and 6,988 for the third year) from 119 schools participating in the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Survey. This study found that 1 in 20 female students surveyed had been raped since the beginning of each school year, with nearly three-quarters of the victims intoxicated at the time of the rape (Mohler-Kuo et al. 2004). Another study analyzing results from a telephone survey of a randomly selected national sample of 4,466 women attending a two- or four-year university found that 1 in 36 students reported having experienced attempted or completed rape during the previous six months of the academic year—a figure that may amount to nearly five percent of female students in a full year and one-fifth to one-quarter of all women over the course of their college career (Fisher, Cullen, and Turner 2000).

The vast majority of campus sexual assaults are not reported to law enforcement. One study that analyzed data from the National Crime Victimization Survey found that between 1995 and 2013, 80 percent of sexual assaults and rapes of female students aged 18 to 24 were not reported to the police. Twenty-six percent of female students who did not report said they felt the incident was a personal matter, 20 percent cited fear of reprisal, 12 percent said they did not think the incident was important enough to report, 10 percent indicated they did not want the offender to get in trouble with the law, and 9 percent said they believed the police would not or could not do anything to help, among other reasons (Sinozich and Langton 2014). Another study found even lower rates of reporting, with just 2.1 percent of incapacitated (i.e. drunk, drugged, passed out, or otherwise incapacitated) sexual assault victims and 12.9 percent of physically forced sexual assault victims reporting the incident to the police or campus security (Krebs et al. 2007).

Many colleges and universities have been criticized for failing to issue punishments that fit the severity of the crime. A study by the Center for Public Integrity that examined data on about 130 colleges and universities receiving federal funds between 2003 and 2008 to address sexual violence found that schools expel only 10 to 25 percent of the students found responsible for sexual assault (Lombardi 2010). More often, perpetrators are temporarily suspended, receive an academic penalty, or face no disciplinary action at all (Lombardi 2010). For victims—who may already be struggling in the aftermath of the assault—the effects of the assault may be compounded by the inaction of their college or university (Lombardi 2010).

Recently, steps have been taken on the federal level to address this issue. In 2014, the Department of Education released a list of 55 colleges and universities under investigation for mishandling cases of sexual violence (U.S. Department of Education 2014), a number that had grown to 94 colleges and universities by January 2015 (Kingkade 2015). The Obama administration also launched the “It’s On Us” initiative, an awareness campaign about sexual assault on college campuses (Somanader 2014; U.S. Department of Education 2014). In addition, the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) imposed new obligations on colleges and universities to report domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking (beyond the required reporting of forcible and non-forcible sex offenses and aggravated assault under the federal Jeanne Clery Act); to notify victims of their legal rights; to abide by a standard for investigation and conduct of student discipline proceedings; and to offer new students and employees sexual violence prevention and awareness programs, among other requirements (American Council on Education 2014).

While such federal action is promising, additional steps can be taken to increase the safety of students on college campuses. A report prepared by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Financial and Contracting Oversight surveyed 440 four-year institutions of higher education and found that while federal law requires an institution to investigate instances of sexual violence, 40 percent of institutions had not conducted a single investigation in the past five years. The report also found inadequate sexual assault response training for faculty and students; a lack of trained and coordinated law enforcement; failure to adopt policies proven to encourage reporting, such as allowing reports to be made via hotline or website; failure to comply with requirements and best practices for adjudication; and a lack of adequate services for survivors (U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Financial and Contracting Oversight 2014).

Violence and Safety Among Teen Girls

Bullying, Harassment, and Teen Dating Violence

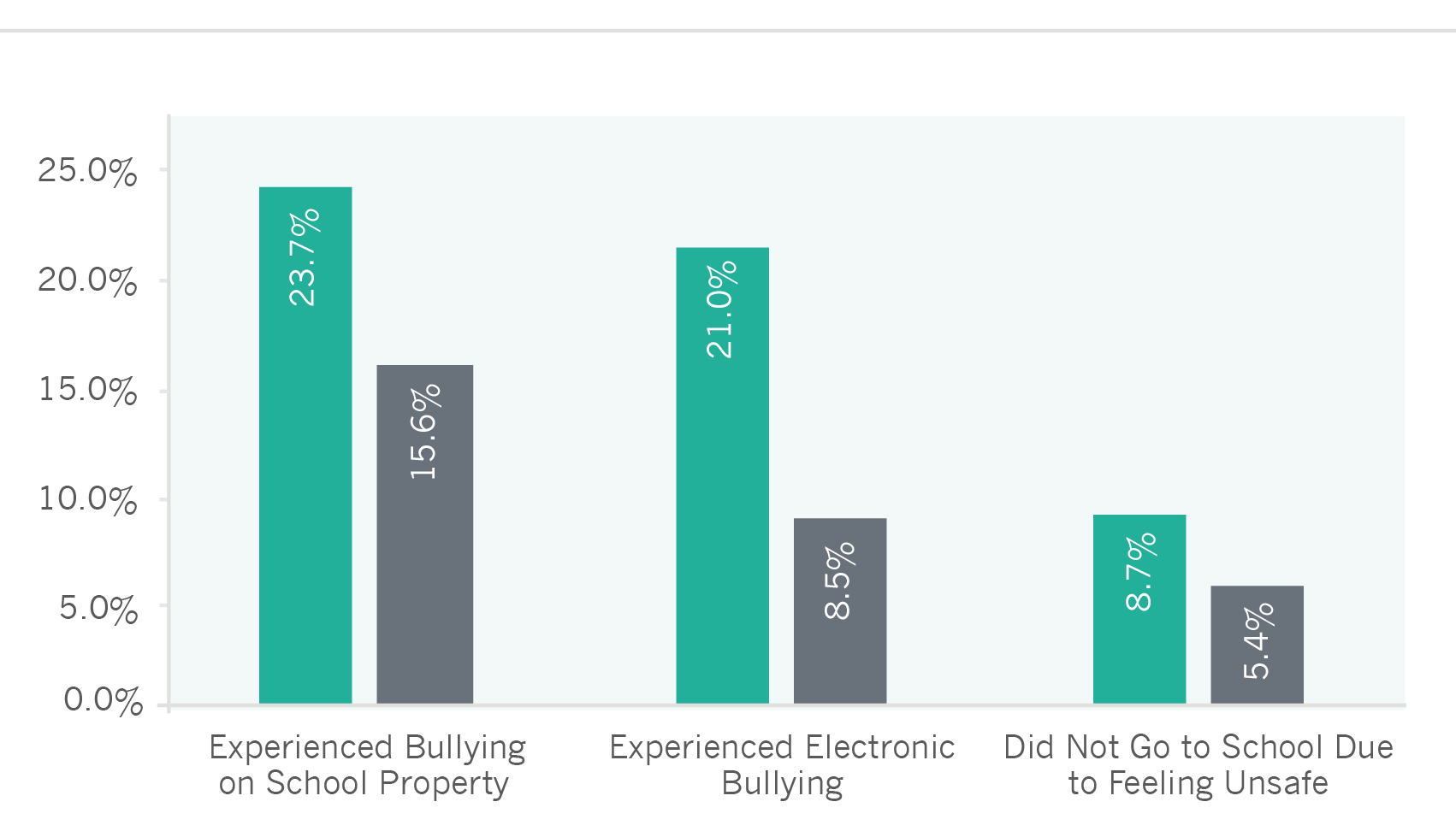

Youth violence—especially bullying and teen dating violence—is a serious public health concern for girls and boys. IWPR analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey finds that nearly one in four (23.7 percent) girls and one in six (15.6 percent) boys reported having experienced bullying on school property one or more times in the 12 months prior to the survey. An estimated 21.0 percent of girls, and 8.5 percent of boys, said they had been bullied in the past 12 months through electronic means such as e-mail, chat rooms, websites, instant messaging, and texting. An estimated 8.7 percent of high school girls and 5.4 percent of high school boys did not attend school at least once in the previous 30 days because they felt unsafe either at school or traveling to and/or from school (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4. Percent of High School Students Feeling Unsafe or Experiencing Bullying by Gender, United States, 2013

Notes: For students in grades 9–12. The percent of those who experienced bullying are for the 12 months prior to the survey; the percent of those who did not go to school is for the 30 days prior to the survey.

Source: IWPR compilation of data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

In addition, 13.0 percent of girls and 7.4 percent of boys who dated or went out with someone during the 12 months before the survey said they experienced physical dating violence (including being hit, slammed into something, or injured on purpose) during this period. About 14.4 percent of girls and 6.2 percent of boys who dated or went out with someone during the 12 months before the survey said they had experienced sexual dating violence during this time, including kissing, touching, or being physically forced to have sexual intercourse by someone they were dating (Figure 7.5).

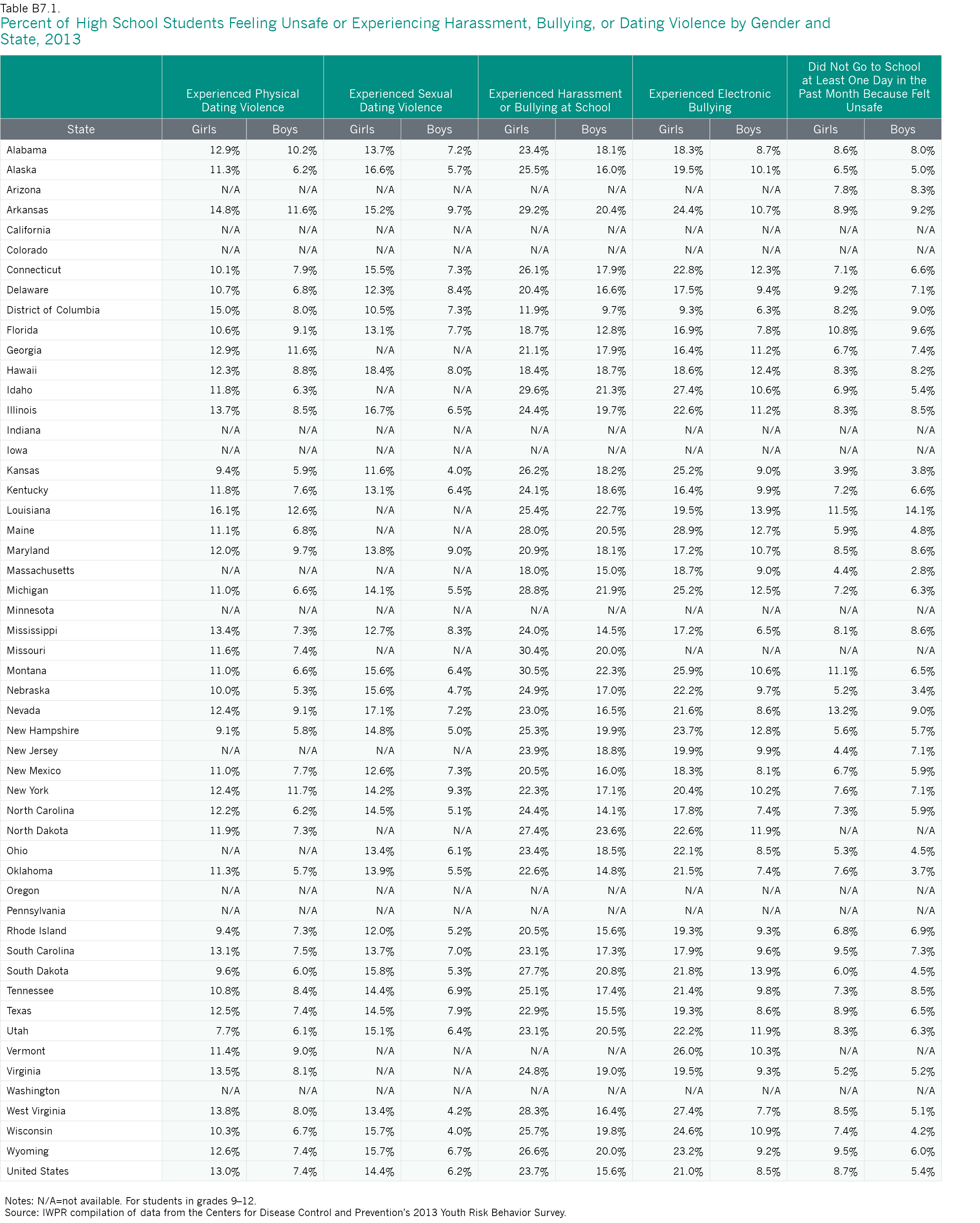

- High school girls in Nevada (13.2), were most likely to say they did not go to school at least once in the past 30 days because they felt unsafe. Girls in Kansas were least likely to report not attending school for this reason (3.9 percent; Appendix Table B7.1).5

- Among the 41 jurisdictions for which data are available, high school girls in Montana, Missouri, and Idaho are the most likely to say they were bullied at school one or more times in the 12 months prior to the survey (30.5, 30.4, and 29.6 percent, respectively). High school girls in the District of Columbia are the least likely to report having been bullied at school (11.9 percent), followed by Massachusetts (18.0 percent) and Hawaii (18.4 percent).

- Maine has the highest percentage of high school girls who have experienced electronic bullying in the past 12 months at 28.9 percent, and the District of Columbia has the lowest at 9.3 percent (data are not available for ten states).

- Louisiana (16.1 percent), the District of Columbia (15.0 percent), and Arkansas (14.8 percent) have the highest shares of high school girls who report having experienced physical dating violence in the past 12 months. Utah (7.7 percent), New Hampshire (9.1 percent), and Kansas and Rhode Island (both 9.4 percent) have the lowest shares.6

- Among the 32 jurisdictions for which data are available, high school girls in Hawaii, Nevada, and Illinois are the most likely to report having experienced sexual dating violence in the past 12 months (18.4, 17.1, and 16.7 percent, respectively). Girls in the District of Columbia (10.5 percent), Kansas (11.6 percent), and Rhode Island (12.0 percent) are the least likely.

Figure 7.5. Percent of High School Students Experiencing Dating Violence in the Past 12 Months by Type of Violence and Gender, United States, 2013

Note: For students in grades 9–12. Includes the percent of students among those who dated or went out with someone in the 12 months prior to the survey who experienced physical or sexual dating violence during this time.

Source: IWPR compilation of data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Several other national studies indicate that as technology has advanced, “electronic” abuse has become a significant issue in teen relationships. For example, a survey of 615 teens aged 13–18 and 414 parents of teens of this age range found that in 2006, 25 percent of teens reported having been called names, harassed, or put down by their partner via cell phone or texting. Twenty-two percent reported having been asked by cell phone or the internet to engage in unwanted sexual activity, and 19 percent said their partner has used a cell phone or the internet to spread rumors about them (Picard 2007). In another study that examined the prevalence of electronic dating abuse among 5,647 seventh to twelfth grade youth from ten schools in three Northeastern states, 29 percent of girls and 23 percent of boys in a current or recent dating relationship said they had been a victim of electronic abuse in the past year (Zweig et al. 2013).

Despite the sizable number of teens who experience violence or bullying, few states recognize teens as domestic violence victims, and state laws vary considerably with respect to the protections and services they provide for youth (Break the Cycle 2010). The nonprofit organization Break the Cycle’s State Law Report Cards assess aspects of each state’s civil protection order laws that are relevant to teens facing domestic and dating violence and provide additional information about services available to teens experiencing these forms of harm. States were assigned grades on the basis of teens’ access to civil protection orders, access to critical services, and school response to dating violence. Only the District of Columbia and six states—California, Illinois, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Washington—received an A.7 Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, and Virginia all received an F (Break the Cycle 2010).

Stalking

Prevalence of Stalking and Common Stalking Behaviors

Stalking is an unfortunately common crime in the United States. A 2009 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that during a 12-month period between 2005 and 2006, an estimated 3.3 million people aged 18 and older were stalked; the majority of victims were female, with those who are divorced or separated especially at risk (Catalano 2012b). Another study found that an estimated 15.2 percent of adult women and 5.7 percent of adult men in the United States have been stalked at some point in their lifetimes (Breiding et al. 2014). Nearly seven in ten victims are stalked by someone they know (Catalano 2012b). Studies have found that intimate partner stalkers are more violent and threatening than non-intimate partner stalkers (Mohandie et al. 2006; Palarea et al.1999), and that partner stalkers tend to stalk their victims more frequently and more intensely than non-partner stalkers (Mohandie et al. 2006).

Stalking is defined as “a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear” (Catalano 2012b). Common stalking behaviors include leaving unwanted messages, sending unsolicited e-mails or letters, spreading rumors about the victim, following or spying on her or him, and leaving unwanted gifts (Catalano 2012b). Many victims suffer serious effects from such behaviors; even when stalking does not lead to physical violence, most victims experience psychological harm (Blaauw et al. 2002; Brewster 1999). Some also experience financial disruption, especially those who are forced to move or leave their jobs (Mullen, Pathe, and Purcell 2009). Research suggests that stalking creates enormous problems for women’s participation in the labor force; many victims experience disruption in their work life, job performance problems, and harassment at work (Logan et al. 2007; Swanberg and Logan 2005). Perpetrators may show up at the victim’s workplace, make threatening phone calls to their co-workers, and use other harassing behaviors that make it difficult for victims to sustain employment (Swanberg and Logan 2005).

Stalking poses a serious threat to personal safety in part because it is difficult to prosecute. Many stalking victims do not report their experiences to the police, most often because they do not think the incidents are serious or consider them a private matter (National Center for Victims of Crime 2002). Even when it is reported, the crime can be difficult for the criminal justice system to address. Stalking can be hard for law enforcement officers to identify, since the perpetrator’s behaviors may be recognized as harmful only when understood within the broader framework of the perpetrator’s course of conduct, which may involve behaviors that in another context would be considered harmless, such as sending letters or making phone calls to the victim. In addition, the unpredictable nature of stalking behaviors makes it difficult to predict if, and when, these behaviors may lead to physical harm (National Center for Victims of Crime 2002).

While stalking is an extremely difficult crime to address and prosecute, states have taken steps to offer victims greater protection. For example, states have passed statutes on stalking and enacted legislation authorizing civil protection orders to increase safety for victims.

State Statutes on Stalking

California enacted the first state stalking law in 1990; the rest of the states and the District of Columbia soon followed suit (National Center for Victims of Crime 2007). In 1996, Congress made interstate stalking a federal offense; subsequent amendments expanded the statute to include stalking via electronic communications, conduct that causes the victim severe emotional distress, and surveillance using global positioning systems (National Center for Victims of Crime 2007).

Although all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government have passed laws that criminalize stalking (Catalano 2012b; National Center for Victims of Crime 2007), the intent of these laws is often not carried out in practice. The laws were created to protect victims from a series of actions that add up to criminal abuse, yet research indicates that prosecutors often do not use stalking statutes to address this crime. They are more likely to charge stalking behaviors as harassment or domestic violence-related crimes, such as assault or violation of a protective order (Klein et al. 2009; Tjaden and Thoennes 2000)—a decision that can be particularly significant in jurisdictions where stalking constitutes a felony and most domestic violence charges are misdemeanors (Klein et al. 2009).

Civil Protection Orders

To address stalking and domestic violence victims’ need to establish safety, states have enacted statutes authorizing civil protection orders (CPOs). First initiated by Pennsylvania in 1976 (Goldfarb 2008), CPOs have been enacted by statute in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (American Bar Association Commission on Domestic & Sexual Violence 2014; Goldfarb 2008).

Civil protection orders are an important legal resource for women experiencing intimate partner or other family violence (e.g., Fagan 1996; Holt et al. 2003; Ko 2002). Research suggests that protection orders reduce violence and the fear many victims experience, although they may be less effective for those who have experienced severe violence (Logan et al. 2009).

Not all victims who want a civil protection order are able to obtain one. Many individuals who pursue this legal recourse face significant barriers, including difficulty in navigating the legal system, discouragement from clerks handling the paperwork, limited hours of access to file the petition, difficulty taking off work or arranging for child care to follow through with the process (Logan et al. 2009), and difficulty meeting a state’s criteria for obtaining a protective order (Eigenberg et al. 2003).

Gun Laws and Violence Against Women

Violence against women is too often fatal: 1,706 women in the United States were murdered by men in 2012 in incidents involving a single victim and single offender (Violence Policy Center 2014). Among the 47 states for which relatively complete data are available, Alaska and South Carolina have the highest rates, at 2.57 and 2.06 per 100,000, and New Hampshire has the lowest (0.30 per 100,000; Violence Policy Center 2014).8 A majority of female homicide victims are killed by men they know, and many are killed by their partners. Between 2003 and 2012, about one-third of female homicide victims in the United States died at the hands of an intimate partner; in many states, intimate partner violence accounted for more than two in five female homicides (Gerney and Parsons 2014).

Guns are the most common weapon used to kill female intimate partners. Between 2003 and 2012, more than half (54.8 percent) of the women who were killed by intimate partners were murdered with guns (Gerney and Parsons 2014). Nationally, the rate of gun violence against women in the context of domestic or intimate partner violence is alarmingly high: one study found that women in the United States are about 11 times more likely to be killed with a gun than non-US women in other highly populated, high-income countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (Richardson and Hemenway 2011).

Federal laws have been passed to protect women (as well as men and children) from gun violence. The Violence Against Women Act of 1994 prohibited individuals subject to domestic violence restraining orders from gun possession, and in 1996 Congress barred individuals convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence crimes from buying or possessing guns (Gerney and Parsons 2014). VAWA 2005 required states and local governments, “as a condition of certain funding,” to certify that their judicial administrative policies and practices included informing domestic violence offenders about the federal firearm prohibitions and any relevant federal, state, or local laws (Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence 2014).

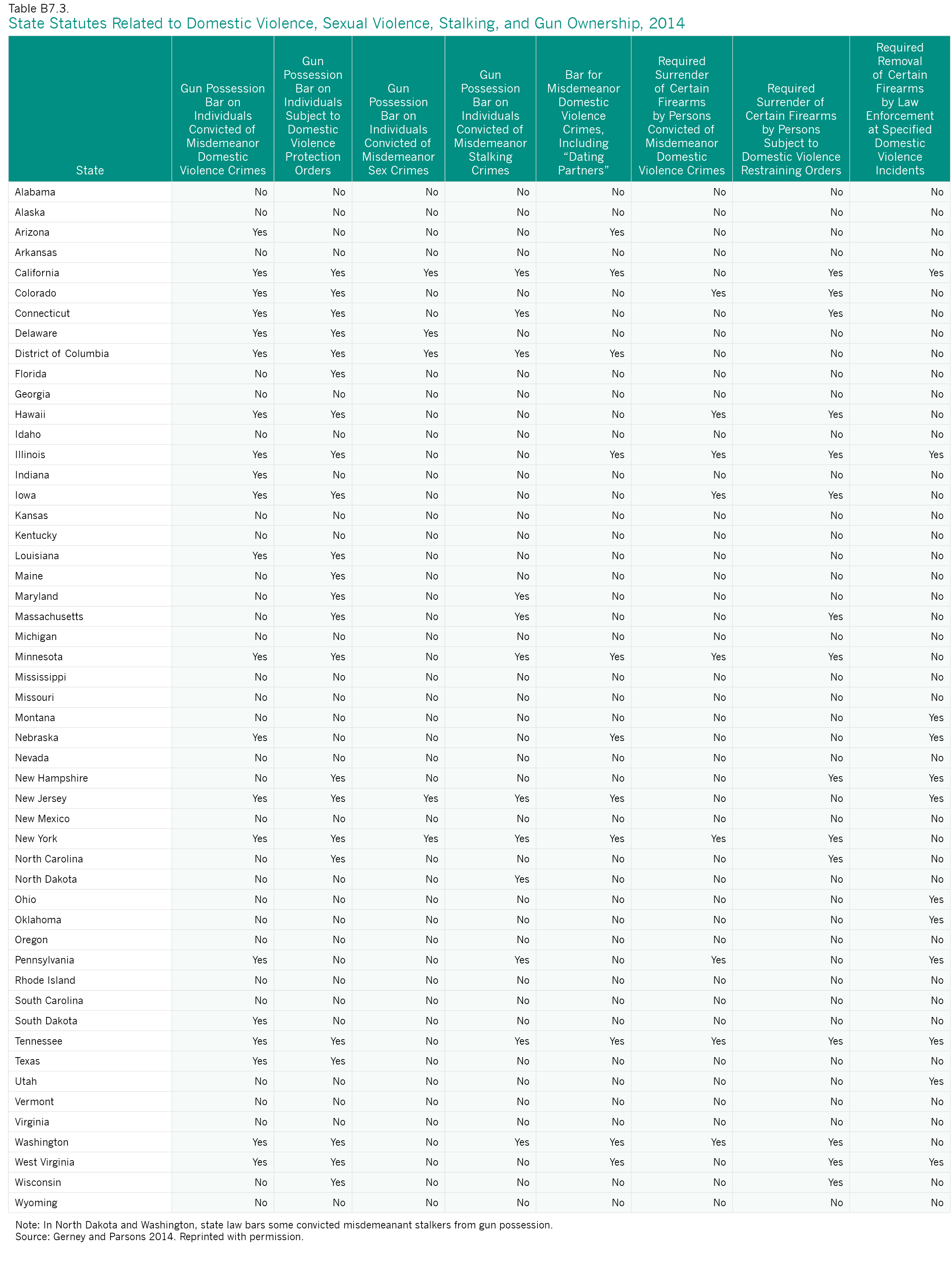

While federal laws on gun violence are vital to protecting victims, they are difficult to enforce, and loopholes in the law remain. State laws can help close these gaps and protect potential victims from harm (Gerney and Parsons 2014). For example, one limitation of federal law is its failure to disqualify those convicted of misdemeanor stalking crimes from gun possession (Gerney and Parsons 2014). As of July 2014, the District of Columbia and nine states—California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—had enacted laws barring all those convicted of domestic violence misdemeanor stalking crimes from possessing guns. Two states—North Dakota and Washington—had passed a statute barring some individuals convicted of these crimes from having guns (Appendix Table B7.3).9

Some states are also taking steps to protect abuse victims by providing records of abusers prohibited from gun ownership to the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). Created by the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 and launched by the FBI in 1998, NICS is a system for determining whether prospective buyers of firearms are eligible to purchase them. Dealers submit the buyers’ names and other information to NICS for a search of databases containing criminal justice information to determine whether the purchaser qualifies for gun ownership under state and federal law. The system, however, has processing problems, including many states’ failure to identify to the NICS individuals who are ineligible to possess a gun due to a criminal history involving domestic violence. As a result, many domestic abusers succeed in purchasing guns from licensed dealers (Gerney and Parsons 2014). Between December 31, 2008, and April 30, 2014, state submissions of domestic violence records to the NICS Index increased by 132 percent. Thirty-six states have submitted such records, but most submit only a very small number. Just three states—Connecticut, New Hampshire, and New Mexico—submit fairly complete records (Gerney and Parsons 2014).

Increasing the submission of records of protection orders to the background check system, for example, could help reduce the number of domestic abusers with guns and the number of women who are at risk for violence. While research suggests that protection orders are associated with reductions in violence (Kothari et al. 2012; Logan et al. 2009), women often remain at risk in the aftermath of securing an order of protection. Ensuring that the NICS has up-to-date information on protection orders that can be used to identify domestic abusers who are not eligible for gun ownership can help ensure the safety of victims.

Some states have taken other measures to protect domestic and intimate partner violence victims from gun violence. For example, some have required a background check for all gun sales; under current federal law, only licensed firearms dealers are required to conduct a background check when completing a gun sale, opening up opportunities for domestic abusers to purchase guns through private sellers. Only 17 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require background checks for at least some private sales (Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence 2013).

Some states have also enacted laws and policies requiring domestic abusers to give up any firearms they own once they are disqualified from gun possession under state or federal law. Only nine states—Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Washington—require surrender of certain firearms when a person is convicted of a domestic violence misdemeanor. Fifteen states require a person to give up certain firearms when they become subject to a domestic violence restraining order (Appendix Table B7.3). These laws, however, are difficult to enforce.

Violence and Harassment in the Workplace

Intimate Partner Violence and the Workplace

Domestic violence and abuse has profound effects on women’s employment and on workplaces. One study estimates that each year women lose almost eight million days of paid work due to intimate partner violence (Max et al. 2004). For many women, the abusers’ actions lead to a decline in their job performance, causing them not only to miss work but to be late, need to leave early, or struggle to stay focused while at their jobs (Swanberg and Logan 2005).

Most states and the District of Columbia have laws to protect the employment rights of domestic violence victims, and some of these laws also explicitly cover sexual assault and/or stalking (Legal Momentum 2014a). Two different types of laws protect victim’s job rights: laws related directly to domestic violence (which offer protections such as the right to leave work to seek services, obtain a restraining order, or attend to other personal matters related to the violence, and/or protect victims from employment discrimination related to the violence) and laws that focus on crime victims more generally (which prohibit employers from punishing or firing crime victims who take leave to appear in criminal court, at least under some circumstances).

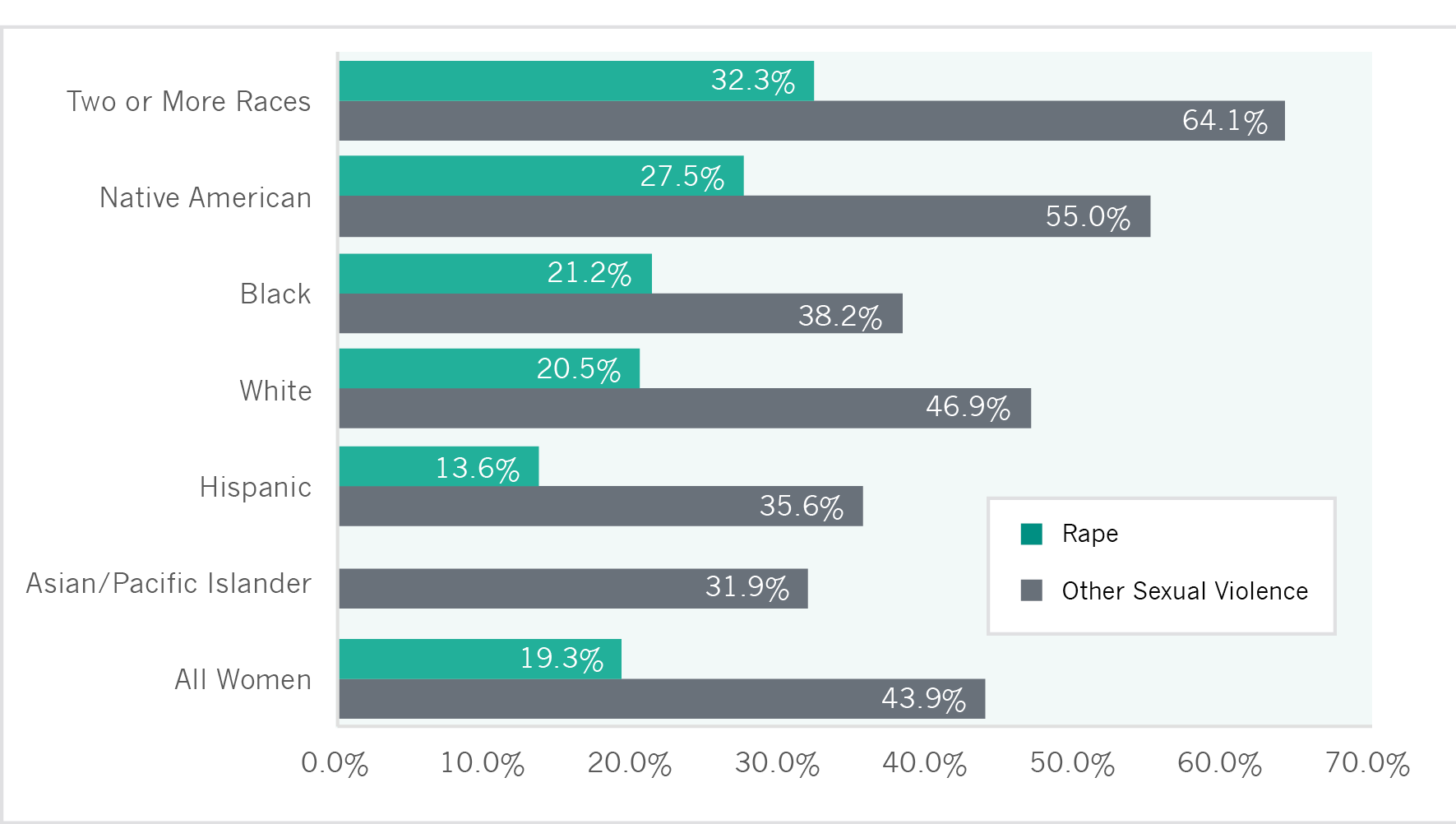

State Employment Protections for Victims of Domestic Violence

As of July 2014, only 15 states and the District of Columbia had employment rights laws for victims of domestic violence, some of which explicitly covered sexual violence and stalking: California, Connecticut, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Washington (Appendix Table B7.2).10 Thirty-three states had general crime protection laws. Nine states did not have either a domestic violence law or a crime victim protection law: Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia (Appendix Table B7.2).

Unemployment insurance laws can also support domestic violence victims. In most states, individuals are not eligible to receive unemployment benefits if they leave their jobs without “good cause.” As of July 2014, 32 states and the District of Columbia had enacted laws that define good cause to include family violence (Legal Momentum 2014b; Appendix Table B7.2). As in the case of laws protecting employment rights, the laws vary from state to state and may or may not explicitly cover sexual assault and/or stalking (Legal Momentum 2014b). Even if a state does not have such a law, victims may still qualify for unemployment benefits under regulations or other provisions11 if they need to leave their jobs. Most states require documentation that violence has occurred for an individual to be eligible for unemployment benefits, though the form of documentation required varies across states, and in some cases is not explicitly specified (Legal Momentum 2014b).

Paid sick time laws can also help victims of violence access services without risking their jobs. Although a host of cities across the nation, including Washington, DC, have implemented paid sick time laws, only three states—California, Connecticut, and Massachusetts—have done so at the state level (A Better Balance 2015).12 All three states include some form of job protected “safe time” for employed victims of domestic violence that allows them to use their sick days to recover from violence or seek help in addressing it, but only one—Massachusetts—also allows workers to use sick time to care for family members who have been victimized (the District of Columbia’s law also covers workers’ children; A Better Balance 2015). Several municipal paid sick days laws in three other states—Washington, Oregon, and Pennsylvania—also provide victims of domestic violence “safe time” to recover from violence or seek help (A Better Balance 2015).13

Workplace Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment in the workplace represents a significant barrier to the career satisfaction and advancement of many women. In 2014, approximately 6,900 charges alleging sexual harassment were filed with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a slight decrease from the year before, when about 7,300 charges were filed (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2015). Many victims, however, do not report incidences of workplace sexual harassment (Huffington Post 2013). Polling data indicate that workplace sexual harassment is widespread: an ABC News/Washington Post poll (2011) of more than 1,000 adults in the United States found that more than one in four women and one in ten men in the workforce have experienced sexual harassment.

Women in certain industries experience workplace harassment at especially high rates. A recent report from the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United and Forward Together or ROC-U (2014), for example, found that although only seven percent of women in the United States work in the restaurant industry, more than 37 percent of the sexual harassment charges reported to the EEOC over an eleven-month period came from women in this industry (ROC-U and Forward Together 2014); many more women experienced harassment they never reported. Similarly, women who work in agriculture jobs—which are predominantly held by men (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014)—experience high rates of harassment and violence, ranging from unwanted touching and comments of a sexual nature to assault and rape in the fields (Morales Waugh 2010). Women who work in these jobs are often migrant workers for whom reporting the harassment can mean risking their jobs, putting their families in danger, and, in some cases, facing deportation (Morales Waugh 2010).

Workplace sexual harassment can have devastating consequences. For the victims, it can result in lower job satisfaction and negative mental and physical health outcomes (Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007). Sexual harassment also has negative effects on organizations, including lower organizational commitment (Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007) and the legal costs associated with any lawsuits. Many organizations have established guidelines to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace and procedures for addressing complaints, yet the pervasive nature of the problem, and extent to which it goes underreported, point to the need for systemic change to address the power dynamics that allow sexual harassment to go unchecked and that often prevent women from participating fully in economic life.

Violence and Safety Among LGBT Women and Youth

LGBT Americans face heightened exposure to hate crimes and physical violence. Although one study that analyzed four national surveys found that across the surveys the proportion of adults in the United States who identified as LGBT ranged from 2.2 to 4.0 percent (Gates 2014), sexual orientation-based hate crimes made up about 21 percent of hate crimes reported by law enforcement in 2013 to the Bureau of Justice Statistic’s Uniform Crime Reporting program (U.S. Department of Justice 2014). This percentage is probably an underestimate given that state and local agencies are not required to release statistics to the FBI, and a number of LGBT survivors of hate violence may not report their abuse to the police (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2014).

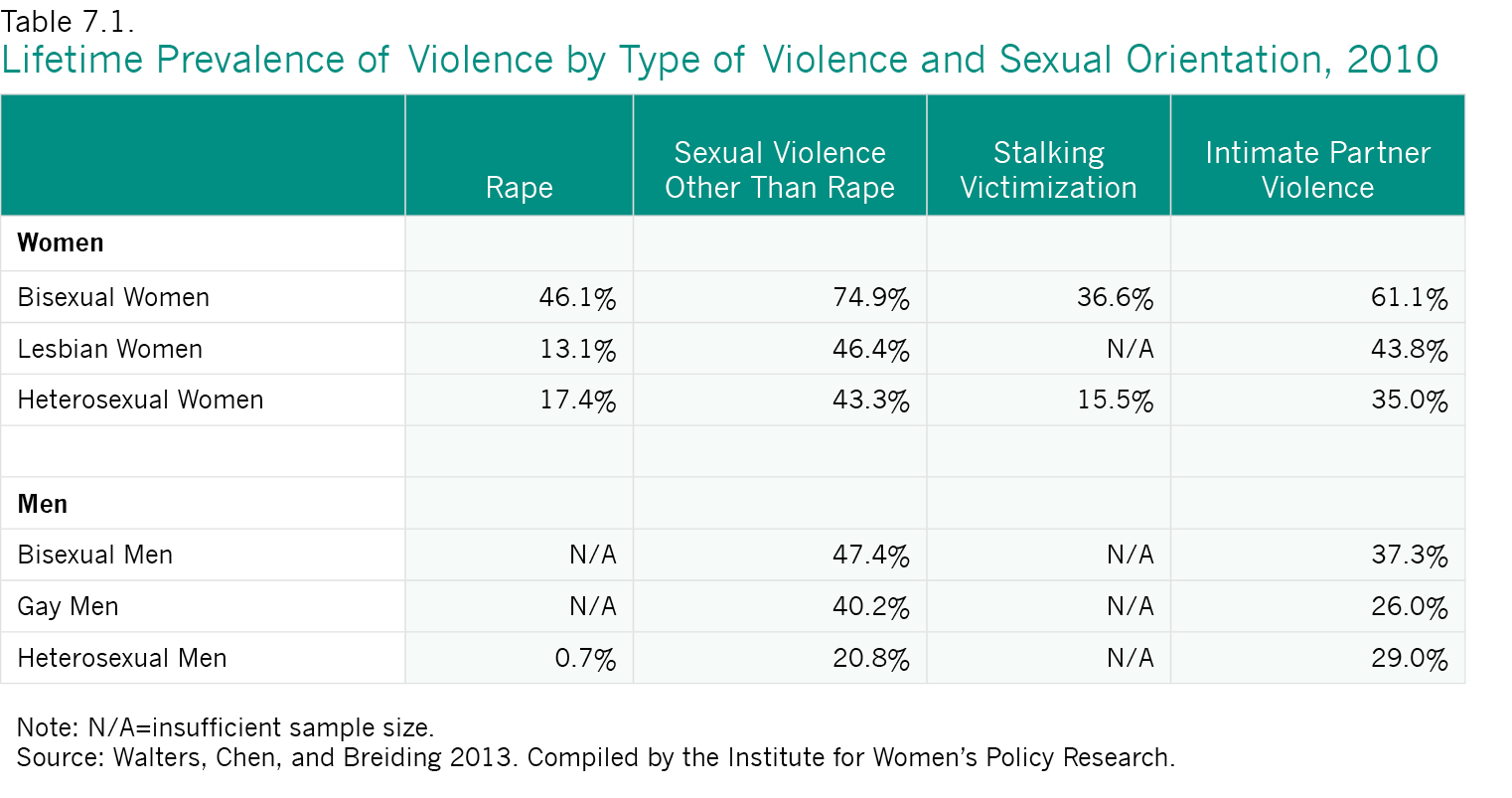

An analysis of the 2010 National Intimate Partner Violence Survey finds that bisexual women are significantly more likely than heterosexual or lesbian women to have experienced violence: 46.1 percent of bisexual women aged 18 and older report having experienced rape, 74.9 percent report having experienced sexual violence other than rape, 36.6 percent say they have been stalked, and 61.1 percent report having experienced intimate partner violence (Table 7.1). Among lesbian and heterosexual women, the prevalence of these forms of violence is considerably lower.

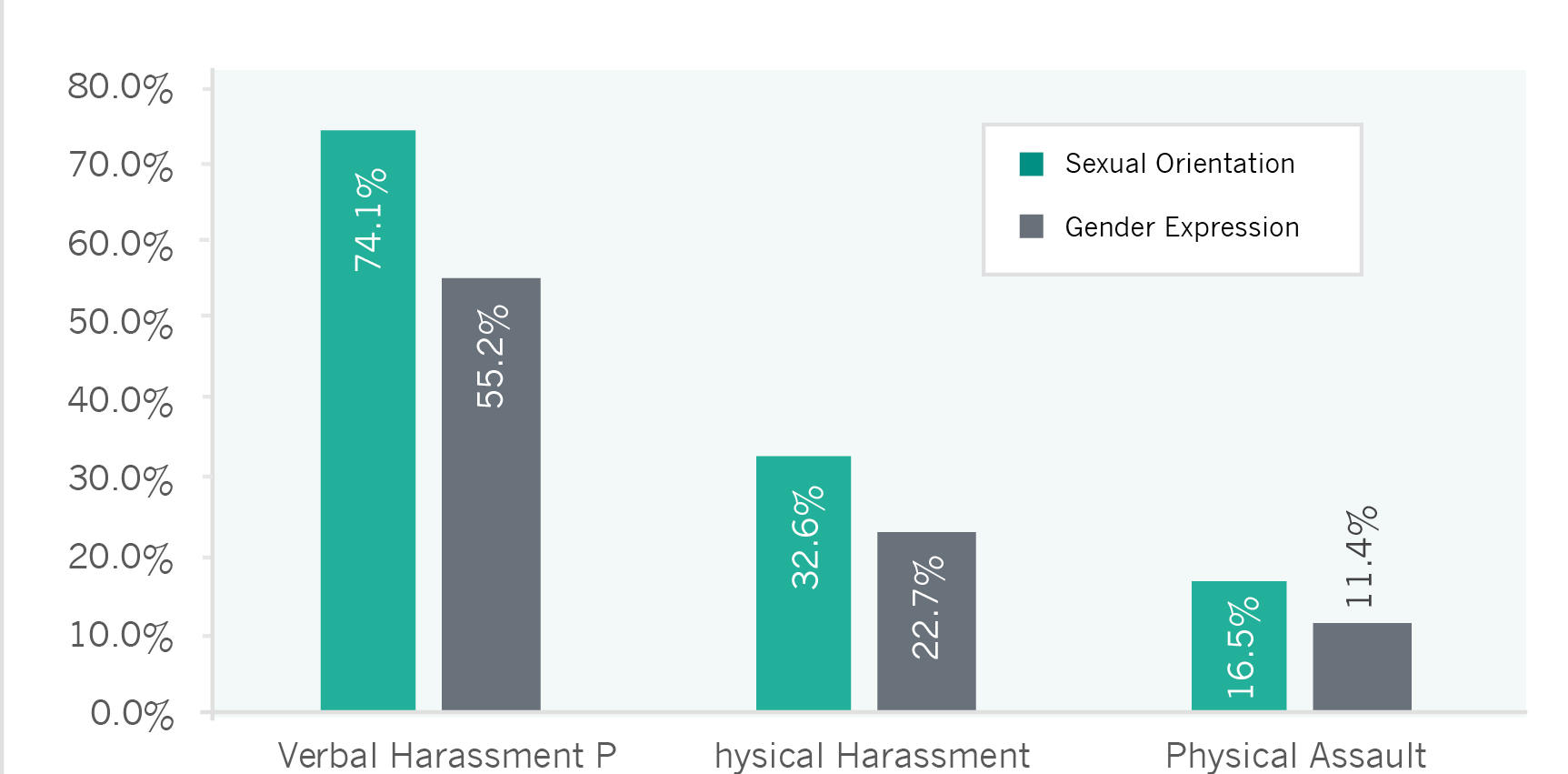

LGBT youth are also vulnerable to violence and discrimination. One study, that analyzed data from the 2013 National School Climate Survey, found that during the 2012–2013 school year, an estimated 74.1 percent of LGBT students aged 13 to 21 were verbally harassed because of their sexual orientation and 55.2 percent because of their gender expression (Figure 7.6). Almost one in three (32.6 percent) were physically harassed (e.g., being shoved or pushed) because of their sexual orientation and more than one in five (22.7 percent) because of their gender expression. A smaller, but still substantial, percentage of LGBT students were physically assaulted because of their sexual orientation or gender expression (Figure 7.6). In addition, nearly half of LGBT students (49.0 percent) experienced cyberbullying, and more than half (55.5 percent) reported personally experiencing LGBT-related discriminatory policies or practices at school (Kosciw et al. 2014). LGBT students who experienced higher levels of victimization had lower GPAs than those who experienced lower levels of victimization. They were also more than three times as likely to miss school in the month before the survey, twice as likely to have no plans to pursue postsecondary education, and had lower self-esteem and greater levels of depression (Kosciw et al. 2014).

Figure 7.6. Percent of LGBT Students Experiencing Verbal Harassment, Physical Harassment, or Physical Assault in the Past School Year Based on Sexual Orientation or Gender Expression, United States, 2013

Note: Students aged 13 to 21.

Source: IWPR compilation of data based on the 2013 National School Climate Survey (Kosciw et al. 2014).

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking occurs when an individual uses force, fraud, or coercion to induce someone to perform commercial sex acts or forced labor and services (Clawson et al. 2009). Although little data exist to document the scope of human trafficking in the United States, one study that draws on qualitative and quantitative data to examine the size and structure of the underground commercial sex economy in eight cities—Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Kansas City, Miami, Seattle, San Diego, and Washington, DC—estimates that the monetary size of this economy was between $39.9 and $290 in 2007 and had decreased in all but two cities since 2003 (Dank et al. 2014). In 2014, the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline received reports of 3,598 trafficking cases within the United States, and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children estimated that one in six endangered runaways reported to them were likely trafficking victims (Polaris Project n.d.). Trafficking victims include women, men, and children (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2006). Those with limited economic opportunities are especially at risk (Action Group 2008), as are runaway or “throwaway” youth (who have been forced to leave their homes), homeless youth, those with prior juvenile arrests, and family abuse victims (Williams and Frederick 2009).

The federal Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 defines trafficking as a federal crime and provides guidance on what a government response to the problem should include (Polaris Project 2014a). Subsequent reauthorizations of the legislation have expanded its scope, and individual states have made important contributions to combating human trafficking. Washington state and Texas passed the first state-level anti-trafficking laws in 2003 (Polaris Project 2014a).

Since then, other states have enacted legislation to combat human trafficking, punish traffickers, and support survivors (Polaris Project 2014a). In its 2014 state ratings on human trafficking laws, the Polaris Project reported that 37 states passed new laws to combat human trafficking between July 2013 and July 2014, and 39 states achieved a “Tier 1” rating, which is given to states that have at least seven points (out of a possible twelve) for having passed significant laws to combat trafficking. Three states—Delaware, New Jersey, and Washington—obtained a perfect score. The two lowest ranked states—North Dakota and South Dakota—have made only nominal efforts to address human trafficking (Polaris Project 2014b). The ratings are based on the presence or absence of specific laws, such as those criminalizing sex or labor trafficking; mandating or encouraging law enforcement to be trained in human trafficking issues; ensuring that elements of force, fraud, or coercion are not required for a trafficker to be prosecuted for the sex trafficking of a minor; mandating or encouraging the public posting of a human trafficking hotline; and granting immunity from prosecution to sexually exploited children, among others (Polaris Project 2014a).

The Consequences of Violence and Abuse

Domestic violence, abuse, harassment, and stalking have a multitude of individual and societal consequences. At the societal level, female victims of intimate partner violence over the age of 18 in the United States lose about 5.6 million days of household productivity and nearly eight million days of paid work each year, which amounts to approximately 32,000 full-time jobs. In 1995, the most recent year for which an estimate is available, the costs of domestic violence in the United States were estimated to be $5.8 billion, with $4.1 billion paying for direct medical and mental health services (the study did not include civil and criminal justice costs; Max et al. 2004). In 2015 dollars, these costs would be about $8.9 billion, with approximately $6.3 billion for direct medical and mental health services.14

Violence and abuse also have profound psychological, health, and social consequences for victims. In the short-term, these forms of harm can result in serious physical injuries. These injuries, however, are only a part of the consequences many women face: the ongoing and controlling nature of abuse can lead victims to experience a range of chronic physical conditions, such as frequent headaches, chronic pain, difficulty sleeping, and activities limitations (Black et al. 2011). Survivors may also experience mental health problems such as depression, suicidality, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Black et al. 2011; Golding 1999); in addition, violence and abuse are associated with negative health behaviors, including smoking, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and substance abuse (McNutt et al. 2002). Over time, the negative physical and mental health outcomes that survivors may experience can interfere with their daily functioning, disrupting their employment and other dimensions of their lives (Loya 2014). In some instances, the unaddressed psychological and social effects of violence and abuse can lead to an ongoing cycle of harm. Research indicates, for instance, that girls who experience physical violence are more likely to be victimized as adults (Whitfield et al. 2003).

Toward the Creation of Safer Communities

These sobering realities point to the need to continue working to enhance our understanding of violence and abuse and to develop effective responses to the multiple forms of harm that women face. At a basic level, this requires improving data collection in the area of violence and abuse by ensuring that survey data are available with sufficiently large samples to allow for analysis at the state level and by race and ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, and other contextual factors. Having improved data will allow researchers to pinpoint the needs of various populations and will help advocates, policymakers, and others to strengthen effective institutional, political, and community responses.

Increasing women’s safety is integral to elevating their overall status. Violence and abuse have devastating consequences that go beyond physical injury to undermine women’s autonomy, liberty, and dignity, preventing them from fully participating in the economy and in civic and political life (Stark 2012b). Often, the non-physical abuse women experience is not or cannot be categorized as a crime and, therefore, falls outside the scope of the legal protections available. Improving effective responses to these forms of harm entails developing laws and policies that reflect a broader perspective on what victims are facing (Stark 2012b), as well as continuing to invest in programs and services that address the threats to safety that prevent women’s full participation in social, political, and economic life.

Appendix Tables

Footnotes

1Other sexual violence includes “being made to penetrate, sexual coercion, unwanted sexual contact, and noncontact unwanted sexual experiences” (Breiding et al. 2014).

2As a result of smaller sample sizes, the 95 percent confidence intervals published by the CDC suggest that the estimates for women of color on rape, sexual violence other than rape, physical violence, and psychological aggression contain more sampling variability than the estimates for non-Hispanic white women.

3Some older women—who were socialized during a time when society provided domestic violence victims with little support—may be reluctant to report abuse (Rennison and Rand 2003).

4As with Figure 7.2, the 95 percent confidence intervals published by the CDC suggest that the estimates for women of color on rape, sexual violence other than rape, and physical violence contain more sampling variability than the estimates for non-Hispanic white women.

5Data are available for the District of Columbia and 39 states.

6Data are available for the District of Columbia and 38 states.

7States were graded individually on 11 indicators using ideal policy criteria determined by Break the Cycle. States that earned eight points or more received an A. Failing grades were given to any state with a score of less than five, and states automatically failed if minors were prohibited from getting civil protection orders or dating relationships were not recognized for civil protection orders (Break the Cycle 2010).

8Illinois has a rate of .24 per 100,000, but only limited data for this state were available (Violence Policy Center 2014).

9North Dakota and Washington state law bars only some convicted misdemeanant stalkers from gun possession (Gerney and Parsons 2014).

10In Colorado and Hawaii, employees must first exhaust their annual, vacation, personal, and sick leave before taking this leave (Legal Momentum 2014a).

11As of January 2014, five states that did not have unemployment insurance laws specifically pertaining to domestic violence victims did have policies, interpretations, or regulations that acknowledge domestic violence may be recognized as a good personal cause for receiving unemployment insurance: Iowa, Mississippi, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Utah (U.S. Department of Labor 2014).

12Connecticut implemented its law in 2013; California and Massachusetts are scheduled to implement theirs in July 2015.

13In addition to these state employment protections, eligible employees can take leave under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act to address their own health problems or the health problems of a family member that resulted from domestic violence (U.S. Department of Labor 2009).

14IWPR calculations using the CPI-U index from the U.S. Department of Labor. The cost due to medical and mental health services needed is likely to be higher than estimated here because medical care expenditures in the CPI-U outplaced overall inflation by 27 percent between 1995 and 2015.